Some info about ecological soundscapes here.

Revenge of the Return of the Sensitive

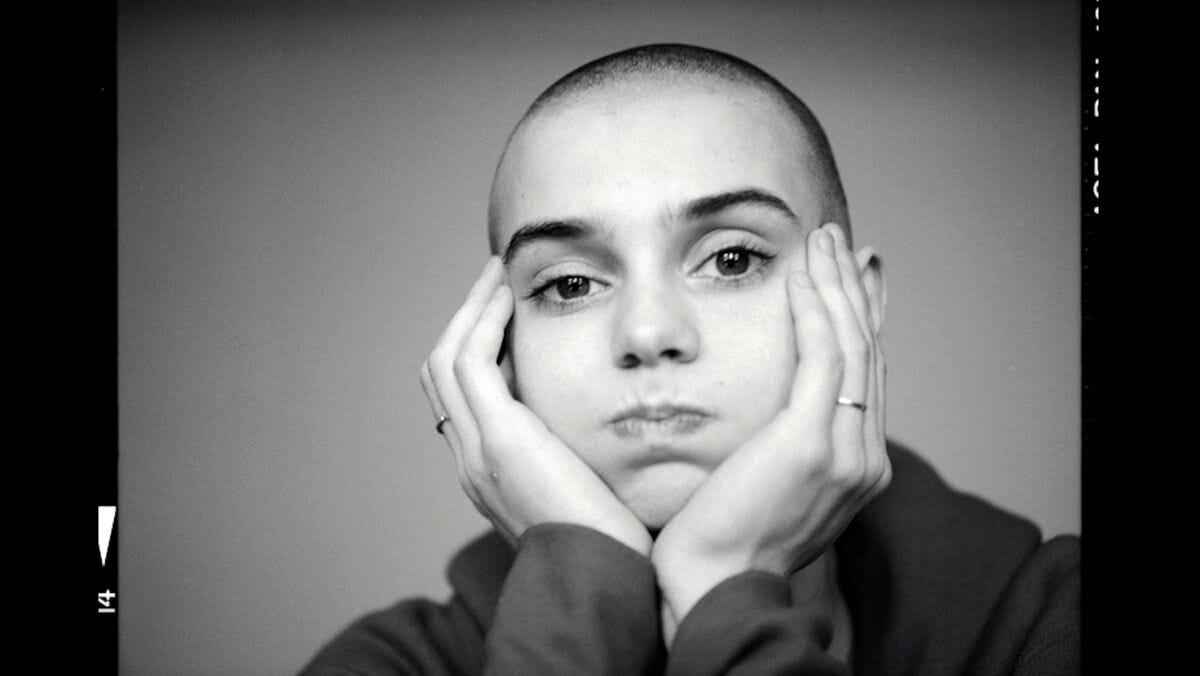

I felt Sinéad O’Connor’s death deeply, and am still kinda reeling. I’ve taken several passes at this essay, and had been working on a long piece before she suddenly left us behind forever. Yesterday, in the middle of hours of her music, I knew what I wanted to say.

To be truthful: I was feeling this exact same anger a week before she died, and here’s why: I was re-watching a DVD in my basement about Canadian music in the 1980s, and turned it off in irritation when narrator-sexual assaulter-misogynist Jian Ghomeshi – whose voice/character I had been ignoring till then – described Mary Margaret O’Hara as a “fragile” artist.

Mary Margaret O’Hara

She was not, and is not, a fragile person. Fact: dumb bullies think anything that reacts to their gorilla touch is fragile. MMOH made one of the greatest albums of our era (voted thusly regularly), but was unusual and had a singular vision, and so the little dogs running the record industry gaslit her for four years, after telling her she could record what she wanted. Turned off, she never recorded another album. We are fortunate that she still makes music, here and there, and she has a happy place in Toronto’s actual music scene (i.e., not Drake). We are lucky to have Miss America in our lives – and MMOH really should have been shown gratitude for her music all along. The little Dog Boys were the problem, and they had all the power.

Luckily for music, Sinéad O’Connor had bigger fists: if O’Hara is 50 percent ghost (my suspicion), O’Connor was about 50 percent bare-knuckle fighter. I wish these two women had known each other, but even if they’d formed a friendship or a supergroup, they would not have been allowed to just be: they’d have been called fragile and weird together. By fools. For no reason.

This is what is making me simmer with rage these last weeks, but I’ve been unable to get at what the feeling really is – and last night I finally figured it out. Through their stories, I am considering how angry I am for myself, about similar stuff.

I ache for O’Connor and steam over MMOH’s mistreatment, not just because they were shit-upon women, or misunderstood artists, but because theirs are stories about how hard and perpetually lonely this shitass world is for weirdos and outsiders and non-conformists. The situation is twisted and dysfunctional and useless and self-defeating, but it persists on and on and on. It goes like this:

Bigger Is Better, According to the Bigger Group

Normal people – let’s call them Group A – treasure their normality. They bind together easily, through performances of agreement, and since they are joining the main body of society, they’re doing a thing that comes naturally to humans. They are as thoughtless about it as the stereotypical American.

Group B – weirdos, artists, non-conformists, neurodivergents, half-angels, etc. – always exist among Group A. They serve a hugely important function, which is to propel ideas and systems forward, to explore new things, to create. They think differently, feel differently, are different. They can’t do all this and also perform the normalcy that maintains Group A, and so the normals-en-masse bash them like ocean waves, and with as much consideration.

Groups A and B are not in any necessary opposition. They are both required. But they are always in tension, because of the bigger group’s unthinking, coercive nature. Weirdos are rolled like rocks in a polisher in the hopes that they’ll smooth out and become suitable pieces of the group. This happens in families, at school, in athletics, at work, in politics. Weirdos are raked and scraped at, informed confidently by powerful idiots that they are simply “wrong” for their entire lives in a way that can’t be explained. In the end, the only ones with anything left of their original vision are either lonely, hiding, or angrily smashing back at the system. Hilariously, Group A doesn’t even know it’s doing this. They have NO IDEA! Because they are a little bit, um, “insensitive.”

On one hand, what the world – the shitty music industry, the shitty press, and the shitty TV watchers who sit in judgment and understand nothing – did to Sinéad O’Connor makes me angry. On the other hand, the fact of her existence – her strength, her fight, her sense of humour, and her deep sense of perspective – gives me inspiration.

Gave.

Gives.

But when I’m listening, I’m hearing pain and indignation, too, and it is sticking deep in my chest. It’s very distracting and upsetting. Here’s the thing people don’t know, the thing I wish I’d been told as a kid so that it all would have made more sense, and the thing I wish the Normal Group knew: It hurts to be treated like a weirdo, and it hurts to be outside the group, and it hurts to be treated like you’re crazy, and it hurts to be gaslit. It is the loneliest, most crazymaking feeling I have ever felt, and my experience of it was so much smaller than Sinéad’s. I was never jeered at by millions. I wasn’t abused like she was. But in her pain, I feel mine.

I was labeled Too Sensitive early on, and often. I was misunderstood by most teachers and disliked by one of my parents. I was told I was “trouble” by incapable idiots, told I was too rough by the smoothly paved, too serious by people distracted by baubles, and too intense to be listened to. My sensitivity was seen as attractive, juicy gravy for my mother’s evil priest friends, but not by anyone else. I was told my perceptions were faulty, my feelings inappropriate, or my ideas naive. The parts of my sensitivity that fools liked were used as needed, and disregarded when inconvenient.

At 10, I was an imaginative, kind, soft kid. By the time I had clawed myself out from under my father’s gaslighting, at around 25, I was fueled by a hate engine and protected by a self-defensive rage. I work hard to contain them. I am still both soft and mean, depending.

I look at Sinéad O’Connor and see about ten million other weirdos behind her, weirdos whose lives were sublimated and twisted, weirdos who became discouraged and surrendered, weirdos in classes who asked the wrong questions, and the social weirdos who didn’t grock the secret rules. They did not all survive. Many killed themselves long ago or erased their strangeness, or stayed high for decades to make existence tolerable.

A Waste of Everything

None of this is necessary. Group A, if it could bother, could shed its competitive and extractive nature, its grabby, unthinking needs, and make room for other kinds of people. The expanded Group A could thrive if it listened more often to the voices of people with different perspectives, becoming more and better. Group A doesn’t do this simply because it doesn’t come naturally, and none of them can see a need for change. They are fully subsumed in the illusion of order and feeling! pretty! great! thank you! You’ll recognize this behaviour dynamic from groups like “Men” and “White People.”

Many among this group – people who “know how things work” and “get along” – work hard to protect the system. Criticism is defended against reflexively, and gaslighting is a primary weapon. Insiders back up each other’s pretenses, agree with each other’s bullshit, and feel so confident while they do it – that’s the individual reward for this conformity, an endless supply of certainty. Fools like my limited and basic father look at the badge they’re given at birth, read their own authority on it, and proceed to act forever as if they’ve earned or deserve their position. They cannot imagine a better way, because it works fine for them.

From my perspective, all of this is lower than low. I despise it. Ignorant and incapable people game every system for themselves, and congratulate themselves on their victory. They punish the unusual, even while they benefit endlessly from the hard, lonely work that the unusual do. They are a nihilistic death machine at this point, killing the planet and all the weirdos on it (while gaslighting anyone who pointed out the impending doom). And they’re still in charge. And they still think they’re doing fine.

I can see killing myself over that nonsense, or dying because of it. There is a limit. My father was and probably still is an insensitive clod, but he was able to make me doubt my mind, my sanity and my worth. It almost killed me. His contribution to the Earth, I tell you just out of spite, was to make plastic bags for Big Oil. Good job! Call him up and say thanks.

Listen: Little, shitty people exist in such numbers and in such an arrangement that original people, weirdos – the inventors of everything, the source of most human development – are made to feel insane. That is fucked.

And you do not know, unless someone tells you, that it is okay to be a sensitive weirdo. (Also, you do not seem to have a choice. Being a weirdo, wrote Lynda Barry, doesn’t happen to you – you get “lucky born it.”)

We’re Here, We’re Weird, etc.

I want to make this declaration, dedicated to the life and voice of Sinéad O’Connor, the patron saint of brave, undefeatable weirdos, and I want other weirdos to spread the word: We are not wrong. It is not wrong to be sensitive, imaginative, or feminine, or weird. The idiots who make us feel that way are kind of primitive, like gorillas: they really shouldn’t be in charge, but sadly, they are. That is a problem. We are not the problem.

And we are not fragile. We are stronger than them – we have to be, to make it through their endless bullshit. We may end up lonely, sad, or hopeless, and we might sometimes opt the fuck out because of that – that isn’t on us. If you’re someone in the In Crowd who’s going Ohhhh, I’ve been an asshole, please share that realization with your friends. And if you are a tired-out weirdo who is feeling seriously done with it, please consider this song sung by two weirdos who found each other for a minute and left it all a little bit better. And also, sorry for all the bullshit out there. It’s not you.

I hope you’re doing alright.

Love,

Santa

He was at the Dylan show when she got booed, called her up. I was surprised too - this was just buried when it came out.

Thank you for saying what so many of us feel everyday. My nephew once called me Uncle Weirdo. I wear it like a badge.